Warning: strlen() expects parameter 1 to be string, array given in /home2/orbman69/public_html/wp-includes/functions.php on line 262

(Last Updated On: )

Date: November 5, 1975

Sighting Time: 6:10 PM

Day/Night: Night

Location: Sitgreave-Apache National Forest, Arizona

Urban or Rural: Rural

Hynek Classification: CE-IV (Close Encounter IV) Abduction of the witness or other direct contact

Duration:

No. of Object(s): Single

Size of Object(s):

Distance to Object(s): 90 feet

Shape of Object(s): Saucer

Color of Object(s): Golden

Number of Witnesses: Multiple

Source:

Summary: In November 1975, a group of six tree-trimmers were driving home from work. The driver stopped the truck when he noticed that a flying saucer was hovering above some nearby trees. Travis Walton approached the craft. He was then knocked to the ground by a blue and white light.

Full Report

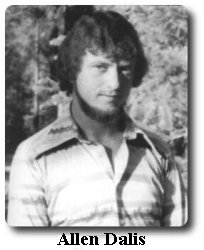

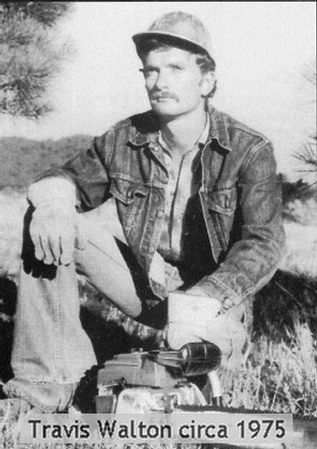

Photo of Travis Walton circa 1975.

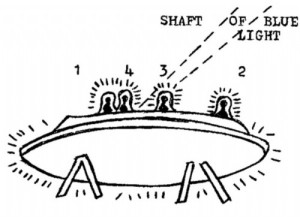

Artistic depiction of the UFO.

Introduction

On November 5th, 1975, one of the more persistently controversial UFO events in history took place in northeastern Arizona. A work team consisting of seven individuals reported encountering a reflective, luminous object the shape of a flattened disc hovering close to their truck on a remote dirt road in the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest. According to the crew, one of their members, Travis Walton, exited the truck and approached the object on foot, at which time he was allegedly struck by a brilliant bluish light or flash and hurled to the ground some distance away. In fear, the other crew members fled the scene, returning after a short period of time to find no trace of the UFO, or of Walton.

The driver of the truck was Mike Rogers, the crew foreman and a personal friend of Walton’s. While fleeing the scene, Rogers reported looking back and seeing a luminous object lift out of the forest and speed rapidly toward the horizon. He, along with the other five witnesses, would eventually be subjected to polygraph (lie detection) examinations regarding the event, the successful outcomes of which catapulted the case into the national spotlight.

Walton turned up five days later, confused and distraught but with fleeting memories of alien and exotic human entities. He was also subsequently subjected to a number of controversial polygraph examinations (Image caption: Travis Walton).

|

|

|

|

|

|

As the first seriously investigated UFO event to involve the disappearance of an individual in conjunction with a UFO sighting, the Walton incident put the honesty of UFO claimants, as well as the validity of lie detection evidence, squarely in the spotlight. A total of thirteen polygraph examinations have been conducted in association with the case, tests which have been the subject of considerable discussion and acrimonious debate.

The Circumstances

An assessment of the Walton case begins with the chronology of the initial encounter on November 5th. The seven witnesses described the UFO as a “large, glowing object hovering in the air below the treetops about 100 feet away” (Mike Rogers) which was “smooth and giving off a yellowish-orange light” (Dwayne Smith). Other descriptions by the various witnesses included “unbelievably smooth”, “flattened disc” with “edges clearly defined”. Rogers and Walton estimated an overall diameter of about twenty feet.

As Walton approached on foot across the clearing, the “UFO began to wobble or rock slightly”, and then emitted a “bluish light [that] came from the machine”, “a blue ray shot out of the bottom of that thing and hit him all over”, “that ray was the brightest thing I’ve ever seen”. This light sent Walton “backward through the air ten feet”, “hurled through the air in a backwards motion, falling on the ground, on his back”, “flying — like he’d touched a live wire”. “The horror was unreal.”

Here are two narrative descriptions of the encounter from two of the crewmen, Mike Rogers and Allen Dalis, as told by polygraph examiner Cy Gilson in his summary of test results in 1993. First, Dalis’ testimony:

“During the pretest interview, Mr. Dalis related the following events that occurred on that day. Mr. Dalis said they had finished work for the day and were heading home. It was almost dark. He saw a glow coming from among the trees ahead of them. As they came to a clearing, he saw the object he called a UFO. Mr. Rogers was slowing the truck down to stop as Travis Walton exited the truck and began to advance towards the UFO in a brisk walk… Mr. Dalis described the UFO as being a yellowish white in color. He said the light emitting from it was not bright but a glow that gave off light all around itself. Mr. Dalis saw Walton reach the UFO, stop and look up at it. He said it looked as if Walton was standing there, slightly bent over, with his hands in his pockets. Mr. Dalis said the UFO began to wobble or rock slightly and he began to become afraid. He put his head down towards his knees. As he did so, a bright light flashed that lit up the area, even the inside of the truck. He immediately looked towards the UFO. He saw a silhouette of Walton. Mr. Walton had his arms up in the air… Mr. Dalis turned towards Mr. Rogers who was in the driver’s seat and yelled for him to ‘get the hell out of here’…”

And as related by Mike Rogers:

“…Mr. Rogers was on the opposite side of the truck from the UFO. He had to bend over slightly to view it in its entirety through the truck windows. He described the UFO to be glowing a yellowish tan color. He could not say if the light emanated from within the UFO or was a lighting system outside, that lit up the UFO. He did say he could see the shadows of the trees on the ground, around the UFO. He said it was round and about 20 feet in diameter. He said the UFO was about 75 to 100 feet from the truck… As Mr. Rogers started to move the truck a brilliant flash of light lit up the entire area, even inside the truck. It was described as a prolonged strobe flash. He did not see a beam of light emit from the UFO and hit Walton. As the flash occurred, Mr. Rogers turned around in his seat to look at the UFO again and saw Mr. Walton being hurled through the air in a backwards motion, falling on the ground, on his back. At this time, Mr. Dalis and someone else yelled to get the hell out of here…”

According to the story, upon returning to the scene, the crewmen searched briefly through the woods, calling Walton’s name. They then proceeded down to the main road and, after some debate, decided to call the police and ask for assistance. They were first met by a Deputy Ellison and subsequently by Sheriff Marlin Gillespie, who would later describe the crewmen as apparently sincerely distressed. The officers and crewmen went back up the hill and searched again with flashlights, eventually calling off the search and making plans for a more thorough manhunt beginning early the next morning.

The next several days were marked by unsuccessful searches for the missing Walton, including some use of helicopters and dogs. Temperatures dropped below zero the first two nights of the search, dimming hope that he was alive. Meanwhile, law enforcement officials were looking for alternate explanations of the event, including the possibility that Walton had been murdered.

In their initial reports, the six crewmen had indicated a willingness to undergo any kind of lie detection test to establish their truthfulness. After the second day of searching, law enforcement officials brought in Cy Gilson, a polygraph examiner from the Department of Public Safety (associated with the state police,) to test all six. Five of the witnesses passed this polygraph examination, while for the sixth, Allen Dalis, the test was ruled inconclusive (unable to assign a reading).

While the successful tests fueled media interest in the case, the inconclusive result for Dalis put some heat on him personally. While some of the crew members, such as Rogers and Walton, had been friends long before the forest service brush-clearing contract, others were only acquaintances, and in the case of Allen Dalis, he and Walton were said to have had some personal animosities.

However, some questions were answered — and others raised — when Walton suddenly returned, apparently confused and distressed, phoning his sister from an Exxon station near the small town of Heber just after midnight the night of November 10th.

In his book “Fire in the Sky”, Walton would later describe his perceptions as he allegedly first regained consciousness: “I regained consciousness lying on my stomach, my head on my right forearm. Cold air brought me instantly awake. I looked up in time to see a light turn off on the bottom of a curved, gleaming hull… Then I saw the mirrored outline of a silvery disc hovering four feet above the paved surface of the road. It must have been about forty feet in diameter because it extended several feet off the left side of the road… For an instant it floated silently above the road, a dozen yards away. I could see the night sky, the surrounding trees, and the highway center line reflected in the curving mirror of its hull. I noticed a faint warmth radiating onto my face. Then, abruptly, it shot vertically into the sky, creating a strong breeze that stirred the nearby pine boughs and rustled the dry oak leaves that lay in the dry grass beside the road. It gave off no light, and it was almost instantly lost from sight. The most striking thing about its departure was its quietness…”

Besieged by media, Walton’s brother Duane reportedly tried to discreetly provide Travis with medical and scientific attention. The Walton brothers would eventually permit the case to be handled by the UFO investigative organization APRO, led by Jim Lorenzon. This resulted in an exclusive relationship with the National Enquirer, which was seeking the “scoop” on the Walton abduction and helping to bankroll APRO’s investigation. The Enquirer, advised by Dr. James Harder of the University of California at Berkeley, arranged for psychological examinations and a polygraph test for Travis. The Enquirer would eventually run a large feature, and APRO touted the case as one of the most important events in UFO history.

Lie Detection Evidence

A total of thirteen polygraph examinations would ultimately be administered in conjunction with the case, a prodigious one as far as the use of polygraph evidence is concerned. A total of nine individuals were tested, including the seven primary participants as well as Walton’s mother and brother. Eleven of the tests were passed, one (the original Dalis test) was inconclusive, and one — the first test of the primary actor Walton — was failed.

In evaluating this polygraph evidence, it is important to back up and consider the validity of lie detection tests in general. Do they work at all? In the domain of applied psychology, lie detection is referred to as the psychophysical detection of deception (PDD). The most common PDD technique is the polygraph, a general term describing tests which measure and correlate a variety of physiological activities (sweat and gland, cardiovascular, respiratory activity) using analog (“conventional”) or computerized instruments.

The polygraph has always been a controversial topic, and much of the public — and many introductory textbooks in psychology courses — treat the matter with considerable skepticism. However, the more strident criticisms of the polygraph were spurred by inadequate earlier techniques, long since soundly rejected by academic scrutiny. Contemporary studies have found moderate but significant validity in the most common of modern techniques, the “Control Question Test” (CQT).

A recent article in the Journal of Credibility Assessment and Witness Psychology reviews the empirical and review literature concerning CQT, and concludes that, “when the ecologically valid laboratory studies and the high quality field studies are considered, both indicate high validity for the CQT.” [1]

The Fifth Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals, in its decision in the U.S. vs. Posado in 1995, overturning “per se” exclusion of polygraph evidence, gave the following overview of the state of the evidence for polygraph:

“There can be no doubt that tremendous advances have been made in polygraph instrumentation and technique in the years since Frye. The test at issue in Frye measured only changes in the subject’s systolic blood pressure in response to test questions. … Modern instrumentation detects changes in the subject’s blood pressure, pulse, thoracic and abdominal respiration, and galvanic skin response. Current research indicates that, when given under controlled conditions, the polygraph technique accurately predicts truth or deception between seventy and ninety percent of the time. Remaining controversy about test accuracy is almost unanimously attributed to variations in the integrity of the testing environment and the qualifications of the examiner. … Further, there is good indication that polygraph technique and the requirements for professional polygraphists are becoming progressively more standardized. In addition, polygraph technique has been and continues to be subjected to extensive study and publication. Finally, polygraph is now so widely used by employers and government agencies alike.”

And according to another court opinion:

“The predominant format employed in the field of polygraphy is the ‘control question’ technique … There is no dispute in this case that the ‘probable lie’ version of the control question technique, when properly employed, is a highly accurate method for detecting deception and possesses the type of scientific validity that satisfies the reliability prong of Rule 702. Through numerous field and laboratory studies, researchers have determined that polygraph examinations using this technique produce results that have an accuracy rate of approximately ninety percent. …

“The most thorough treatment of polygraph admissibility issues can be found in two district court opinions from Arizona and New Mexico [Galbreth and Crumby] … both courts found that polygraph theory and technique had been tested by the scientific method and repeatedly validated in field and laboratory studies, subjected to stringent peer review and extensive publication, shown to have a remarkably low error rate when properly applied by a skilled polygrapher, enjoyed substantial acceptance within the scientific community, and was widely used within government and industry.” [2]

Significant, and probably appropriate, obstacles remain before polygraph evidence finds a widespread and well-defined place in the courtroom, most notably with respect to the required standardization of examiner training, and in the ratification of techniques that are demonstrated proof against any physical and mental “countermeasures” that may be attempted by fraudulent claimants. However, a picture of significant validity and progress emerges.

It appears that there is sufficient evidence of the validity of polygraph testing to justify its careful use as one form of supporting evidence in the evaluation of UFO and other “extraordinary” claims. Polygraph results have the possibility of being most effective when used in multiple witness situations, where test error can be minimized across multiple subjects, and the possibility of “gross hoax” (i.e. the probability that the witnesses as a whole are lying about an event) can be rejected to a potentially high degree of confidence.

However, the responsible use and evaluation of lie detection evidence requires a careful consideration of which kinds of tests are well-grounded in scientific validity and which are not.

Overview of the Walton Polygraph Evidence

The initial tests of the six witnesses, performed by Cy Gilson while Walton was still missing, were CQT-format examinations. The questions he asked primarily addressed the possibility of some non-extraordinary foul play at work, but pointedly questioned the witnesses regarding the veracity of the reported UFO event. As mentioned previously, five of the six passed, with the one inconclusive result.

In the next test to be performed, a private investigator named John McCarthy was hired to test Walton relatively soon after his reappearance. McCarthy ruled Walton deceptive, and the test results were regrettably suppressed by APRO and the National Enquirer. (This test will be discussed in detail below.)

A follow-up examination of Walton by George Pfeifer ruled Walton truthful. After allegations aired by critics, Walton’s mother and brother also took and passed polygraph tests administered by Pfeifer.

Twenty years later, in 1993, Cy Gilson retested key participants Travis Walton, (foreman and Walton friend) Mike Rogers, and Allen Dalis (the original “inconclusive” result), using a state-of-the-art computer-scored CQT methodology. All three passed.

The significance of the unanimous passing of competently administered CQT examinations by all six witnesses is considerable. Assuming independent tests, the odds of gross hoax (all participants lying about the UFO encounter) is less than one-tenth of a percent using the reasonably conservative figure of 70% for test accuracy, and on the order of one in a million using the 90% figure suggested by field tests. In short, relatively strong evidence that some kind of real event took place. On the basis of such evidence, APRO praised the case as one of the most important in history.

The Debunker Strikes Back

Media attention attracted both supporters and critics of the UFO phenomenon. One of the most well-known UFO skeptics, Phil Klass, became deeply involved in the case, and vociferously denounced it as a hoax.

Klass published numerous white papers on the case, criticizing witnesses and attributing damaging comments to key players. He would eventually present his completed criticisms in his books “UFOs — the Public Deceived” and later in “UFO Abductions — A Dangerous Game”.

Some of the negative evidence publicized by Klass is worthy of attention and, at the very least, a raised eyebrow. Most memorably, Walton’s brother Duane made a number of curious comments during an interview with ufologist Fred Sylvanus during Walton’s disappearance, suggesting that he was convinced Travis had embarked on a great adventure. For example, when asked if he believed Travis would be returned, Duane replied: “Sure do. Don’t feel any fear for him at all. Little regret because I haven’t been able to experience the same thing.” (Supporters would later characterize this as Duane’s attempt to defuse the popular notion of Travis as a victim, lab rat or hunting trophy.)

But Klass frequently pushed the evidence well past where it was willing to naturally bend. For example, in his discussion of the Sylvanus interview, which took place at the search site and involved both Duane and Mike Rogers, Klass wrote of Rogers (underlined, and in all caps): “BUT AT NO TIME DURING THE HOUR-LONG INTERVIEW DID ROGERS EXPRESS THE SLIGHTEST CONCERN OVER WHETHER TRAVIS MIGHT HAVE BEEN INJURED OR KILLED”.

The actual tape includes such comments as these from Rogers: [Recalling event:] “…we’re going to have to go back. I agreed, you know, we couldn’t leave him over there if he was hurt, which he certainly looked to me like he received some kind of [pause] something, some kind of injury, I don’t know if it just stunned him or hurt him. Since we haven’t found him we don’t know but [big sigh, pause]…” And: “…no tracks, no pieces of clothing, no blood, no nothing. I mean there was no trace of it, and there was no trace of him. Some of the guys started crying; I remember I started crying…”

Klass aggressively tried to characterize Walton as a “known” “UFO freak”, while Walton denied any unusual interest in the subject prior to his abduction. For example, Klass wrote in his June 1976 paper: “…I asked [Dr. Kandell] whether Travis or Duane had indicated any previous interest in UFOs during his November 11 discussions and examination. Dr. Kandell replied: ‘They admitted to that freely, that he [Travis] was a ‘UFO freak’, so to speak … He had made remarks that if he ever saw one, he’d like to go aboard.'”

Walton was eventually able to obtain and present Klass’ original transcripts of the conversation, which presents a different picture than that suggested by Klass’ cut and paste quotation: Kandell: They admitted to that freely, that he was, you know, a “UFO freak”, so to speak. He’s interested in it. Klass: Which one? Kandell: Travis. He had made remarks before that if he ever saw one, he’d like to go aboard, this and that. So, yes, that was mentioned. That was out. Klass: When was that? Was that when you and Dr. Saults were there or when more of the people were there? Kandell: No, that was, I think, subsequently, it came out. I don’t know whether it was that Friday night, or it could have been that I, that it was in the newspapers, that somebody else might have mentioned it. Klass: But you heard it from their own lips? Kandell: I think so. I think so. I can’t be 100-percent positive. But if I didn’t, it was discussed. They didn’t deny that. That wasn’t denied. Continuing to pound out a negative characterization of key participants, Klass writes in “UFOs: The Public Deceived”:

“Clearly Rogers feared that at least one member of his crew would fail [a follow-up polygraph] test, regardless of who was accepted as the examiner. [Investigator Bill] Barry’s book quotes Rogers as saying, “[Witness] Steve [Pierce] told me and Travis that he had been offered ten thousand dollars just to sign a denial. He said he was thinking about it… So I told him, ‘Then you’ll spend the money alone, and you’ll be bruised.'” The latter suggests that Rogers was threatening Pierce with physical harm if he recanted.”

Klass’ presentation suggests a hoax organized by Rogers and Walton and held together with raw physical threats (although the reader is left with some confusion as to why Rogers would be admitting this to investigators.) But again, this citation appears in a rather different light when contrasted with the original passage from which Klass is quoting (from Barry’s book:)

“According to Mike Rogers, ‘Steve told me and Travis that he had been offered ten thousand dollars just to sign a denial. He said he was thinking about taking it. We asked him, ‘Even though you know it happened, would you deny it just for the money?’ He said maybe he would; he was thinking about it. So I told him, ‘Then you’ll spend the money alone, and you’ll be bruised.” “

Klass’ creative use of ellipses artfully shifts the context of the comments. Klass also deceptively injects the term “recant” (with its connotation of a public confession of error), when clearly Pierce was talking about falsely denying the event in return for money.

(Bill Barry, whom Klass is quoting, offered a blistering review of Klass’ investigative demeanor, for the record: “His method of dealing with their evidence was harsh, smug, superior, unfair, and sometimes worse. And when push came to shove, and evidence could not be impugned, he simply ignored it and omitted it from consideration.”)

Klass eventually focused on his “forest contract theory” for hoax motive, wherein Walton and Rogers were staging the hoax as a way to get out of the forest service contract via an “act of God” provision. According to all parties, Rogers was in fact close to defaulting on the contract. Klass documents this, citing Forest Service Contracting Officer Maurice Marchbanks.

However, Klass failed to relay Marchbanks’ opinion of the plausibility of such a motive, as Marchbanks is reported elsewhere stating flatly, “There was no way such an alleged hoax could benefit Rogers.” Forest Service Contract Supervisor Junior Williams concurred: “He had no reason — I didn’t see that he had anything to gain, as far as his contract was concerned, or anything else, to conjure up a story of this kind.”

Klass on the Polygraph Evidence

Klass attacked the original Gilson tests on the grounds of insufficient questioning regarding the UFO incident. He quoted Gilson as saying, “That one question does not make it a valid test as far as verifying the UFO incident.”

This, however, contradicted Gilson’s written word at the time. And in 1993, in preparation for retesting, Mike Rogers asked Gilson to state for the record whether his opinion of the original tests had changed. Gilson replied:

“Today, in 1993, I am still of the same opinion that they were valid examinations and the results were conclusive on the five. Even though there was only one question asked that related to the UFO sighting, it was a valid question and the results proved none of you were lying when stating you saw an object that you believe was a UFO. … I hope this letter will satisfy you, and anyone else, that my beliefs in the results of those examinations, are the same today as they were in 1975.”

But however lackluster Klass’ case on all these counts, the crown jewel of his campaign was clearly the discovery of the initial, failed polygraph test of Travis Walton. On a tip, Klass tracked down John McCarthy and found himself in the possession of a genuine scoop: a polygraph test failed by the primary actor Walton and suppressed by the ufological group APRO and the National Enquirer.

APRO’s advisors, such as Dr. James Harder, had felt the test was inconclusive as a result of Walton’s emotional instability. The Enquirer accepted this and ordered the followup Pfeifer test. Yet such excuses would ring hollow to the ears of many observers.

In fact, Klass’ discovery of the McCarthy test turned many ufologists and much of the public against the case. For example as recently as 1997, popular ufologist Kevin Randle panned the case as a hoax in his book The Randle Report, arguing that, due to its proximity to the original events, the McCarthy test “spoke volumes” about Walton’s truthfulness.

The test would also achieve a sort of urban legend status among UFO skeptics. For example, Anson Kennedy of Georgia Skeptics was quoted on Robert Sheaffer’s web site as saying:

“But the real ‘bombshell,’ as Klass describes it in his book, was the fact that Walton had failed an earlier polygraph examination miserably and this information had been suppressed by APRO, which had been proclaiming the Walton case ‘one of the most important and intriguing in the history of the UFO phenomena.’ This test was administered by John McCarthy, who with twenty years of experience was one of the most respected examiners in the state of Arizona. His conclusion: ‘Gross deception.’ Proponents of the Walton case never mention this examination.”

The story, including the embellishments (McCarthy “with twenty years of experience was one of the most respected examiners in the state of Arizona”) could be traced directly, of course, to Klass.

The McCarthy Test and Polygraph Methodology

Unfortunately, neither Klass nor modern critics such as Randle seriously address the issue of polygraph methodology. John McCarthy in 1975 was still using what is called the “Relevant/Irrelevant” (RI) examination format. Test transcripts were forwarded by Allan Hendry of CUFOS to Dr. David Raskin, a published scholar and recognized authority on the polygraph, who described the technique as “unacceptable” and “thirty years out of date”.

A cursory examination of the literature readily confirms the degree to which the RI technique is held in low regard. The aforementioned academic review of polygraphy states brusquely, “Of the three techniques discussed in this paper, there seems to be general agreement in the scientific literature that the Relevant-Irrelevant Test lacks validity”.

Crucial is the issue of why, specifically, RI tests have been found to be unreliable. The same court review that praises CQT as “a highly accurate method for detecting deception” explains that:

“The relevant/irrelevant technique has been determined by researchers to produce an unacceptably high number of ‘false positive’ errors (because even an innocent subject will recognize the significance of the relevant question and may react to it) and has generally been discarded in favor of other techniques that have been shown to have a higher degree of reliability.” [3]

Dr. Charles Honts, another heavily published scholar of PDD techniques, and also an authority who has testified as an expert witness in key court cases involving polygraph evidence, concurs that “the relevant/irrelevant technique has been conclusively shown to be an invalid technique in published scientific research.” [4]

Specifically, “the relevant/irrelevant technique is known to produce a large number (80+%) of false positive errors (the truthful fail the test). A failed RI test should be given no weight for any purpose.”

In other words, under the right conditions, you would want to bet — and bet heavily — that a truthful respondent will fail a RI polygraph exam.

And the conditions of the McCarthy test are not particularly ideal. Descriptions of Walton’s extreme agitation are universally available, even from cynical skeptics such as Enquirer reporter Jeff Wells: “Our first sight of the kid was at dinner in the hotel dining room that night. It was a shock. He sat there mute, pale, twitching like a cornered animal. He was either a brilliant actor or he was in serious funk about something… The kid was a wreck and it was all the psychiatrist could do to get him ready for the lie-detector expert we had lined up.”

Additionally, the Walton brothers experienced McCarthy as hostile and disbelieving, which (if true) can also increase the risk of false positive error. On tape, McCarthy interrupts Walton 28 times, for example berating him when he is clearly confused about dates, snapping “Where have you been, in a vacuum?”

In the context of an RI test, these issues simply establish that we have exceptionally good reasons to discount the results. Klass’ heralding of the “bombshell” McCarthy results, as well as Kevin Randle’s contemporary argument that the McCarthy test “speaks volumes” about Walton’s truthfulness, are in striking contrast to Charles Honts’ comment that a “failed RI test should be given no weight for any purpose”.

The 1993 Gilson Tests

Of the remaining polygraph tests, the most significant are those administered by Cy Gilson, including the 1993 CQT exams of key players Walton, Rogers and Dalis. Critics have floated a number of reasons as to why these tests should (also) be considered suspect. For example, Kevin Randle cites the opinion of a polygraph examiner who believes that Walton could have become comfortable with his fraud in the retelling, and thus passed the followup tests in 1993.

I asked Charles Honts to comment specifically on Randle’s suggestion that the tale gets easier in the retelling. He replied, “I know of no scientific evidence that suggests that the passage of time, per se, would affect the validity of the polygraph. In fact the available research fails to show such effects, but no study has looked at time intervals in terms of years. … I think the suggestion that telling a story over and over would make you comfortable with the story and enable you to pass the test is most unlikely.”

Others have suggested, based on McCarthy’s feelings in 1975 that Walton was trying to consciously “distort” his breathing to beat the test, that Walton has trained himself in countermeasures to beat polygraph examinations. To this possibility, Honts replies, “Possible, but very unlikely. Research has shown that under the proper conditions there are techniques that people can learn to enable some of them to beat comparison question test. However, this research also shows two additional things: Sophisticated training is necessary for the countermeasures to work, and the computer analysis that Gilson used is very hard to beat, much harder than the numerical scoring used by polygraph examiners. In fact the CAPS/CPS computer scoring is THE BEST COUNTER-COUNTERMEASURE known.” (emphasis original.)

Honts was able to provide additional background on the examiner and technique employed in the tests in question: “The computer analysis program that Gilson used has been the topic of peer-reviewed scientific publication and has been shown to be valid see, Kircher and Raskin (1988) J. Applied Psychology.”

“I have known Cy Gilson for about 14 or 15 years. He was a respected police officer and polygraph examiner while he worked for the State of Arizona. I have seen his polygraph work in other cases and it has been of high quality. My impression of Cy Gilson is that he is not given to wild flights of fancy. I know of nothing that would suggest to me that he is anything but an honorable and honest man.”

Gilson’s letter of summary regarding Walton’s test can be viewed online at: http://www.anw.com/ fire/CyGilsonReport.htm

Dalis and Rogers received even higher confidence scores, with statistically derived p-values of 99%.

Epilogue

The Gilson tests were conducted during preparation for the 1993 film adaptation of Walton’s experiences, also titled Fire in the Sky, produced by Paramount Pictures. The tests had been sponsored and monitored by a skeptical investigator named Jerry Black, who initially contacted Paramount demanding to know why they were making a movie about a known hoax. Black reopened an independent investigation into the case, interviewing such key participants as George Pfiefer, John McCarthy, Sheriff Marlin Gillespie and the Forest Service officials.

On the heels of the film and the Gilson tests, Walton was able to present a summary rebuttal to his critics in his 1996 book release (most notably in the form of an 85 page appendix dissecting his primary accuser, Klass.) In it he quotes Jerry Black on his eventual assessment of the case:

“There’s no question in my mind that the clincher, as far as Travis Walton himself is concerned, was his agreeability to take the polygraph in the face of realizing that he had really nothing to gain and everything to lose at this late point and date. The film was already made, he had his money; if he was really lying he would have been a fool, under the circumstances, to take the test with nothing to gain and everything to lose. [This] showed me that he had nothing to fear, that in his mind he knew, he *had to know* that in his mind he was telling the truth as he knew it. He knew full well that it was going to become public record. The questions were tight. Everything in the polygraph just confirmed my total investigation.”

So what happened to Travis Walton in the mountains of Arizona in 1975? The horrific on-craft alien encounter depicted in the 1993 Paramount film is almost entirely a fictional presentation, although the bulk of the film, pertaining to the human drama, is broadly accurate and well presented. Walton’s actual memories of his experience include a frightening but brief and unviolent confrontation with large-eyed alien beings (with pupils, as opposed to standard abductee “greys”,) followed by an encounter with silent and seemingly bemused humans of exotic appearance who escorted and tranquilized him. Are these memories — some assisted with hypnotic regression — an accurate and literal reflection of reality? Like the UFO problem itself, the ultimate explanation of the Walton disappearance remains a protracted mystery.

——————————————————————————–

References:

1. The Journal of Credibility Assessment and Witness Psychology, 1997, Vol. 1, No. 1, 9-32, “Truth or Just Bias: The Treatment of Psychophysiological Detection of Deception in Introductory Psychology Textbooks”, by Mary K. Devitt, Oklahoma State University, Charles R. Honts, Boise State University, and Lynelle Vondergeest, University of North Dakota. Numerous citations and sources.

A fuller excerpt:

“The most commonly used test in the field is the Control Question Test. We will focus most of our analysis on validity studies of the CQT. … A recent review (Honts & Quick, 1995), found four field studies of the CQT (Honts, 1994b, now in press; Honts, & Raskin, 1988; Iacono & Patrick, 1991; and Raskin, Kircher, Honts, & Horowitz, 1988) and two of the CKT (Elaad, 1990; Elaad, Ginton, & Jungman, 1992) that were able to meet the stringent requirements for a useful field study described above. Three of the field studies (Honts, 1994; Honts & Raskin, 1988; Raskin et. al., 1988) produced accuracy rates above 90%. The independent evaluators in the third study (Iacono & Patrick, 1991) produced a high false positive rate, although the accuracy rate of the original examiners exceeded 90%.

[…]

“Laboratory Studies Concerning Forensic Settings. A recent meta-analysis of 15 laboratory studies (Kircher, Horowitz, & Raskin, 1988) of the Control Question Test indicated a wide range of validity estimates. One study found near chance results, while six of the studies produced moderate validity estimates, and eight of the studies report validity coefficients of 0.7 or better. In four of the studies, the validity coefficients exceeded 0.8. The Kircher et al. meta-analysis noted that these laboratory studies differed widely in their ecological validity. Some studies used mock crimes and procedures that closely modeled field conditions while other studies were very artificial and used unrealistic procedures. Moreover, the Kircher et al., meta-analysis indicated that those laboratory studies that most closely modeled field conditions produced the highest accuracy rates.

[…]

“Although there is controversy, the empirical and review literature concerning PDD suggests the following conclusions: There is little support for the Relevant-Irrelevant Test, but this test is in frequent use only in employment settings. The laboratory and field data concerning the Control Question Test are mixed. However, when the ecologically valid laboratory studies and the high quality field studies are considered, both indicate high validity for the CQT.”

2. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, U.S. vs. Posado, citing in particular:

Kircher, J. C., Horowitz, S. W., & Raskin, D. C. (1988). Meta-analysis of mock crime studies of the control question polygraph technique. Law and Human Behavior, 12.

Raskin, David C., The Polygraph in 1986: Scientific, Professional and Legal Issues Surrounding Application and Acceptance of Polygraph Evidence, 1986 Utah L. Rev. 29, 72 (1986)

3. U.S. District Court, Southern District of Georgia, U.S. vs. Gilliard.

4. Honts suggests a related article on the topic of the relevant-irrelevant method by Horowitz et al in the first issue of the 1997 vol of the scientific journal Psychophysiology. A selected listing of Dr. Honts’ professional publications and reports on the polygraph is available online at http://truth.idbsu.edu/honts/cv2.html

More Articles on this Case

The Official Travis Walton Website

Travis Walton

The Walton experience is unequivocally the best documented case of alien abduction ever recorded. This is the official website of Travis Walton, and about his UFO abduction case.

The Travis Walton Case

APRO Bulletin, Vol. 24 No. 5 (Nov 1975)

On the morning of the 6 th of November, 1975, Arizonans were electrified by the news that, on the night before, a young Northern Arizona woodcutter had “disappeared in a flash of light emitted by a UFO”. It is the main attempt of this presentation to set the record straight on behalf of Travis Walton, who has been harassed and lied about by some individuals in the media and UFO buffs as well.

Related Reports

Warning: strlen() expects parameter 1 to be string, array given in /home2/orbman69/public_html/wp-includes/functions.php on line 262

5 min read

1993: Polygraph Test of Travis Walton – Article